Paolo Colombo: The Acclaimed Italian Artist Who Knows Art Inside Out Explains Why He Splits His Time Between Athens and the Rest of the World

Paolo Colombo holds a special position within the art world as both a fascinating artist and an accomplished curator, a global career that started in the 1970s. Born in 1949 in Turin, Italy, he was the first European to exhibit at the today-known-as MoMA PS1, New York, in 1977, and until 1981, he was active as a young artist in Athens, Greece. In the mid-80s, while creating his own family, he shifted to art curation, initially as a research assistant at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, and soon after, working for the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia. Important positions in the field followed, with him being the Director of the Centre d’Art Contemporain in Geneva from 1989 to 2000 and curating the 6th International Istanbul Biennial in 1998-99. Between 2001 and 2007, Colombo was the curator of the Museo Nazionale Delle Arti del XXI Secolo (MAXXI) in Rome, built by Zaha Hadid. He was hired when it opened as the first museum in Rome solely dedicated to contemporary art. In 2007, Colombo returned to Athens, his adopted home base, resuming his work as an artist, after a 25-year hiatus while traveling and maintaining his curatorial practice worldwide. Among various capacities, he has been an Art Advisor for the Istanbul Museum of Modern Art. He was also a curator for the 3rd Thessaloniki Biennale in 2011 and the 2nd Mardin Biennial in 2012, as well as an associate producer of 3 award-winning features in Cannes, Berlin, and Venice. In 2015, he curated for the Pinacoteca Giovanni e Marella Agnelli in Turin, and in 2017 the Iraqi Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. In a similar role, he has also collaborated with the Benaki Museum, the Museum of Cycladic Art, and the Onassis Stegi Cultural Center, in Athens.

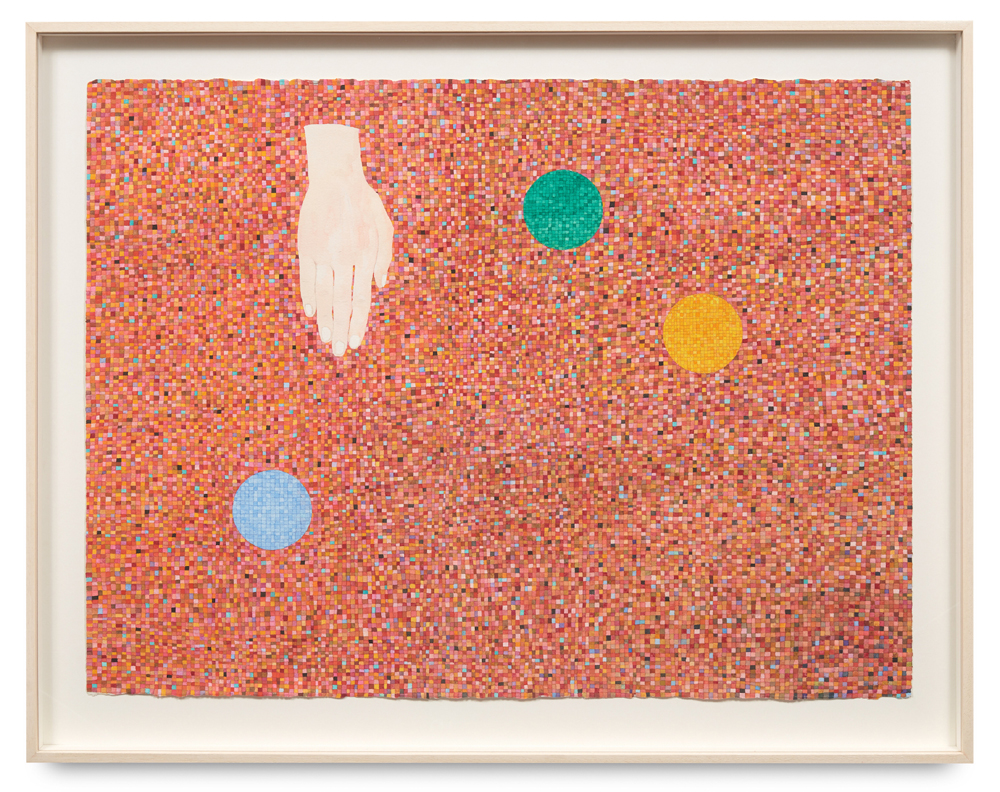

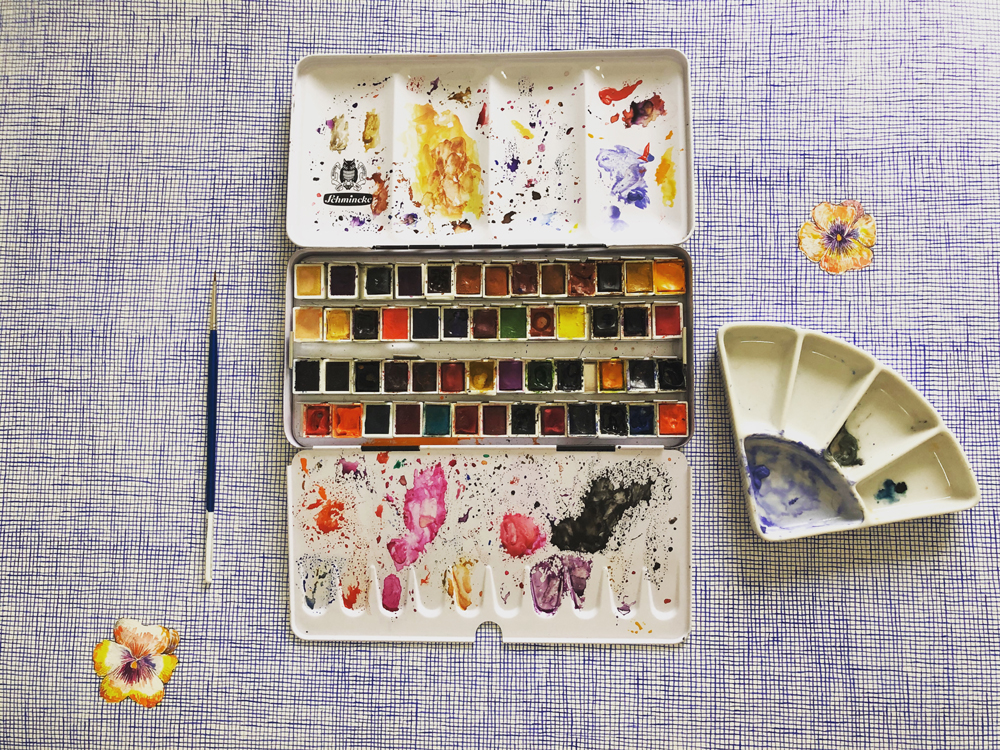

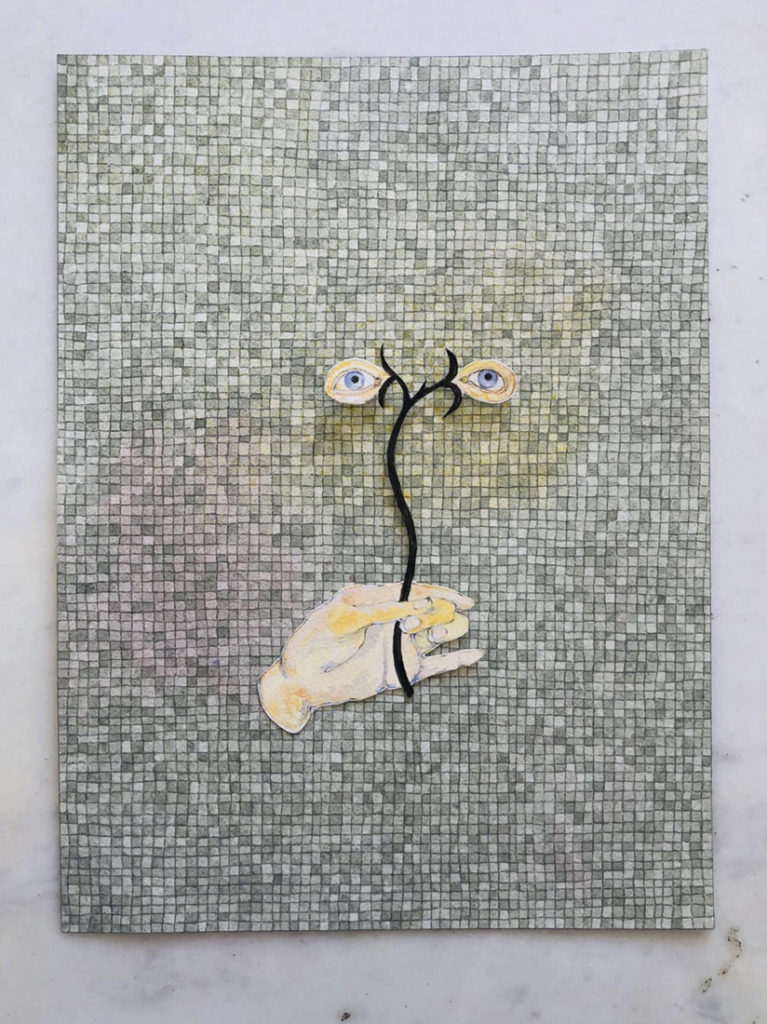

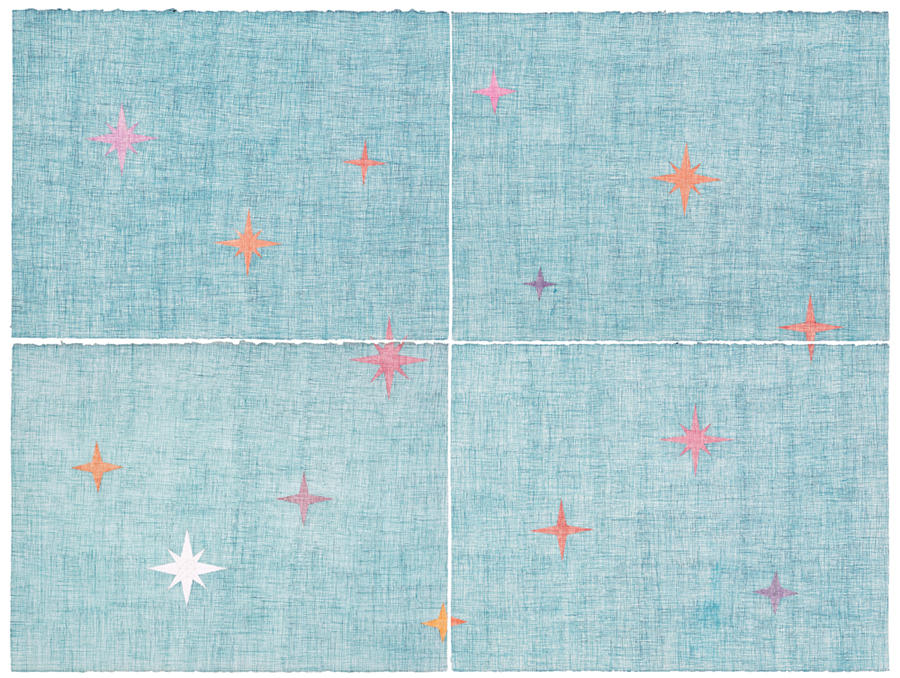

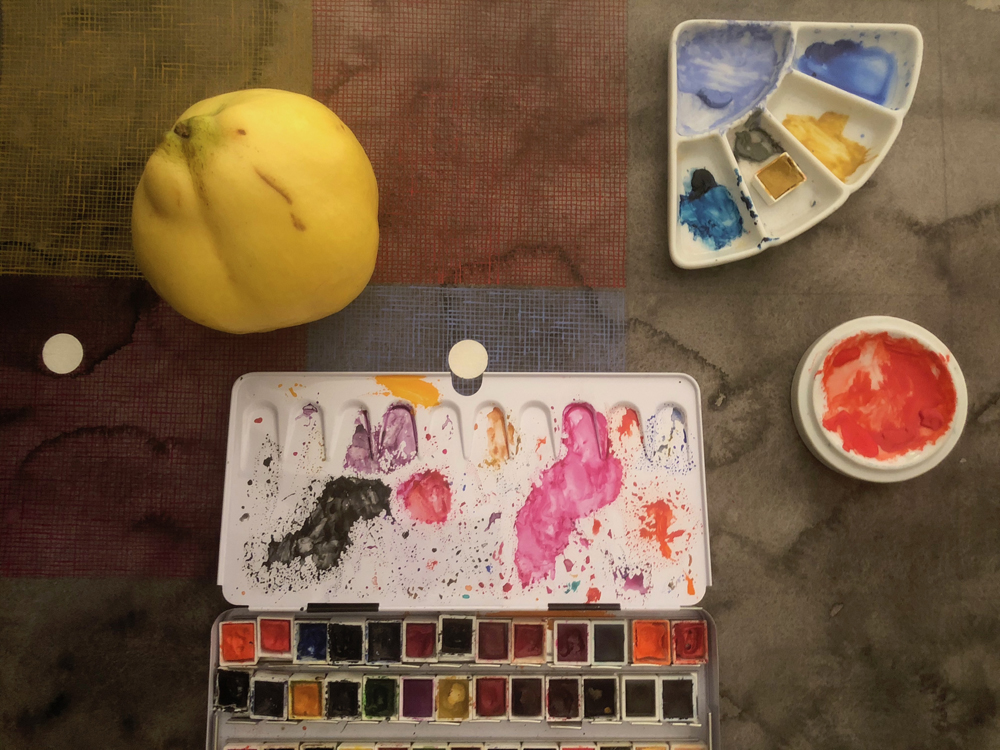

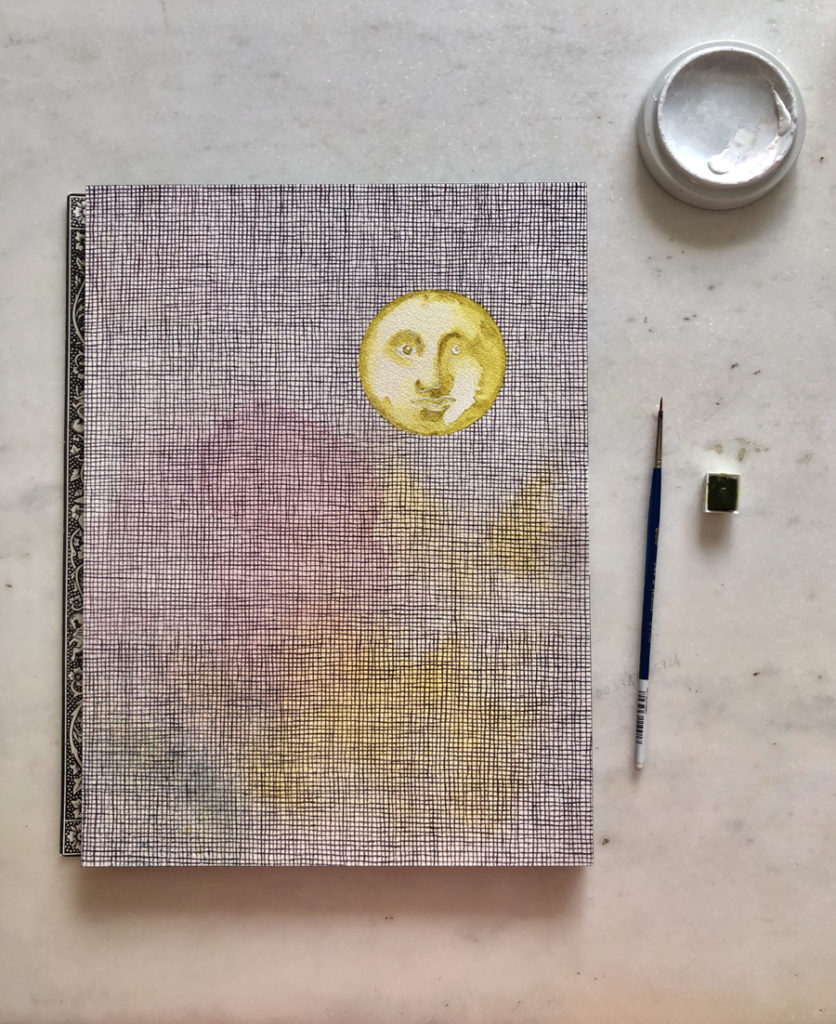

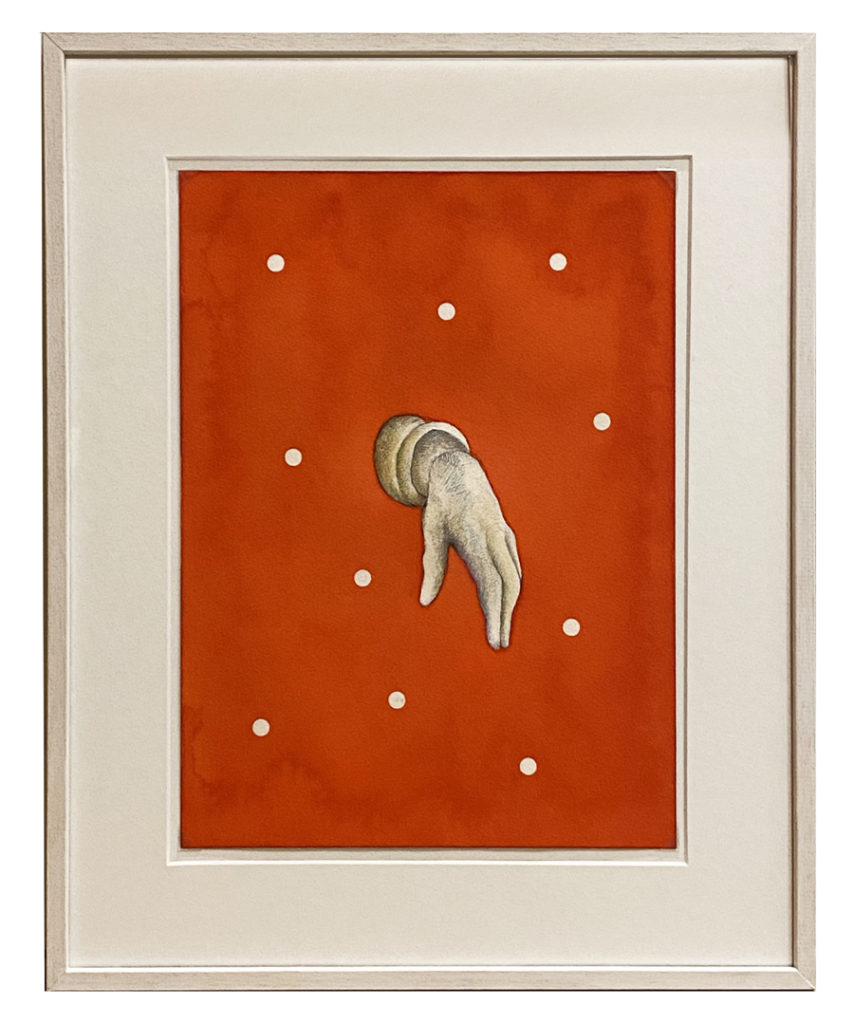

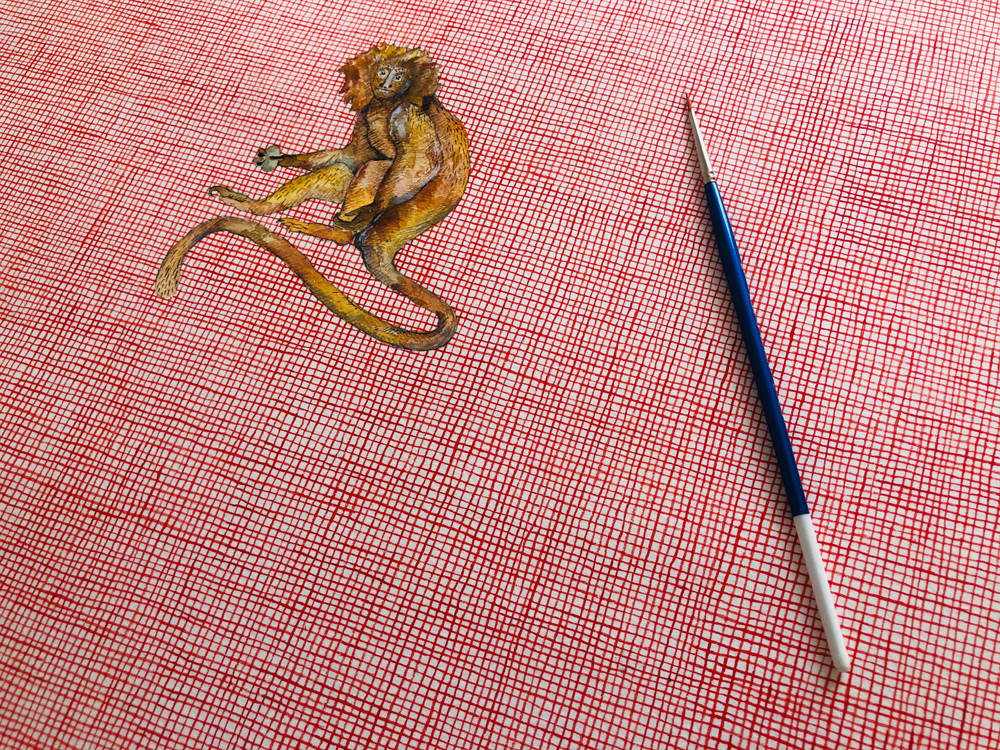

The totality of these undertakings sounds impressive, yet this is only one side of his. As an artist painting with watercolors and drawing with a pencil, Colombo is equally praised and distinguished. His practice is intimate and lyrical, mixed with published and yet-to-be-published poetry of his, love of nature, and a meditative approach. His imagery often features living things, including flowers and animals. In Athens, at the Bernier/Eliades Gallery, the artist’s second solo exhibition was on from January 16th to February 15th, 2020; his first one in this gallery took place back in 1980. Soft washes of color prevailed in dream-like compositions that included a signature backdrop of fine lines mimicking the warp and weft of a woven fabric or mosaic-looking chequered squares. His first solo show in the UK happened May-June 2017 at the Tristan Hoare Gallery in London, where he also exhibited in February-March 2020, alongside Kiki Smith’s sculptures in a show titled “Of Birds and Monkeys.”

Along with accolades, Colombo has been blessed with friendships, probably the result of his charismatic and generous personality. Stéphanie Artarit, the French author of Assouline’s Athens Riviera book we interviewed recently, has been one of them over the last couple of years. They first met at awarded writer Radhika Jha‘s home, their mutual friend. Artarit describes him as very sweet and curious about people; the opposite of egocentric, an attribute which is quite rare of an artist. She sees his work as delicate and admires him for being extremely cultivated, a true gentleman, not superficial at all. In her own words, “he made an effort to read my novel Devil’s Variations in the original in French. This shows who Paolo is. Someone who is trying to understand people, who they are, what they are doing…” In this interview, the esteemed journalist, writer, and psychoanalyst asks the artist important questions about his life and career choices, a story of action and tranquility at the same time.

Which was the first educational experience in your life that sealed the deal of you becoming a painter?

I studied in the German part of Switzerland from the age of 12 to 18, on top of a mountain. There was only the boarding school and a farmhouse. I had a very good art teacher who suggested we buy gouaches and thick, good-quality paper. For the third lesson, he came to class with a book, Tonio Kröger by Thomas Mann. He read the lines when Tonio sees Hans Hansen and Inge Holm far away on a North Sea beach. Tonio is leaning on a beached boat, and he sees Hans and Inge, the two loves of his adolescence, coming together to kiss. Our teacher, whose first name was Innocente (Innocent), then asked us to illustrate the scene. A world opened. I knew then and there that painting was all I wanted to do in my life. I was twelve, one of three students in a very small class.

Would you like to get back in time and reflect on your first visit to Athens in 1965? What were your initial impressions?

I came to Athens on a trip when I was 16. I remember that there was countryside and sheep on Syngrou (today an avenue) between Hadrian’s Gate and the seashore. When I arrived at that Gate on my way from the sea, I looked up, on my left, and saw the Acropolis for the first time.

When did you come back, and what do you remember from that trip?

I returned after graduating from high school. I spent three months in Crete, painting many oils on canvas. When I returned to Rome, my suitcase full of paintings and art supplies was lost at the airport. That very day I decided that I was going to buy watercolors and a pad of paper, and would always carry my art with me.

Was listening to the radio and Greek songs a way to learn to speak the Greek language?

When I arrived in Athens in 1977, I found an apartment to rent that was (at the time) the highest apartment in Athens, the retiré (top floor) of 75 Marasli street, a short block above Hoidá on the Lycabettus. There, I painted the whole day, listening to the radio. I learned the words for Prime Minister, news, and parliament very quickly. And “words of the heart” from songs. When you learn a new language, there is a time that you can combine the few words you know in the most effective and charming way. Everything you say is black or white, with no grey in between. Listening to the old Greek song “To pasoumi,” meaning “The slipper,” by Rita Abatzí, I heard the phrase “san ti perdika patas” meaning “you walk like a partridge,” which I tried at once as a supreme compliment. As such, it was received with a nice sense of humor from my friend! When you start learning a language, you can get away with murder using lines from popular Greek songs, like “your beauty is like a moon’s reflection on the sea,” “a knife in my heart,” or singing in March the full version of “mia Kyriaki tou Marti” meaning “a Sunday in March” by Dimitra Galani.

When and how did you meet your gallerist Jean Bernier of Bernier/Eliades?

In 1977. A friend from New York suggested we meet, so we met and soon began a long conversation. After a few months, Jean Bernier asked me (I remember the exact words): “Do you only make friends, or do you also make art?” A studio visit followed, and my first show with the gallery was in 1980.

Who were the first artists you met when you came to live in Greece in the 70s?

I met Vlassis Kaniaris, Alexis Akrithakis and Nicos Baikas. And several foreign artists who came to Athens to show at the Bernier/Eliades Gallery. It was a very small art community then; we all saw each other all the time.

Based on your illustrious global career as a curator and your important work as an artist, I’m looking to understand what parts of your personality and philosophy make you curate art and what parts make you create art. Do you love being on each of the sides equally, or do you prefer one over the other?

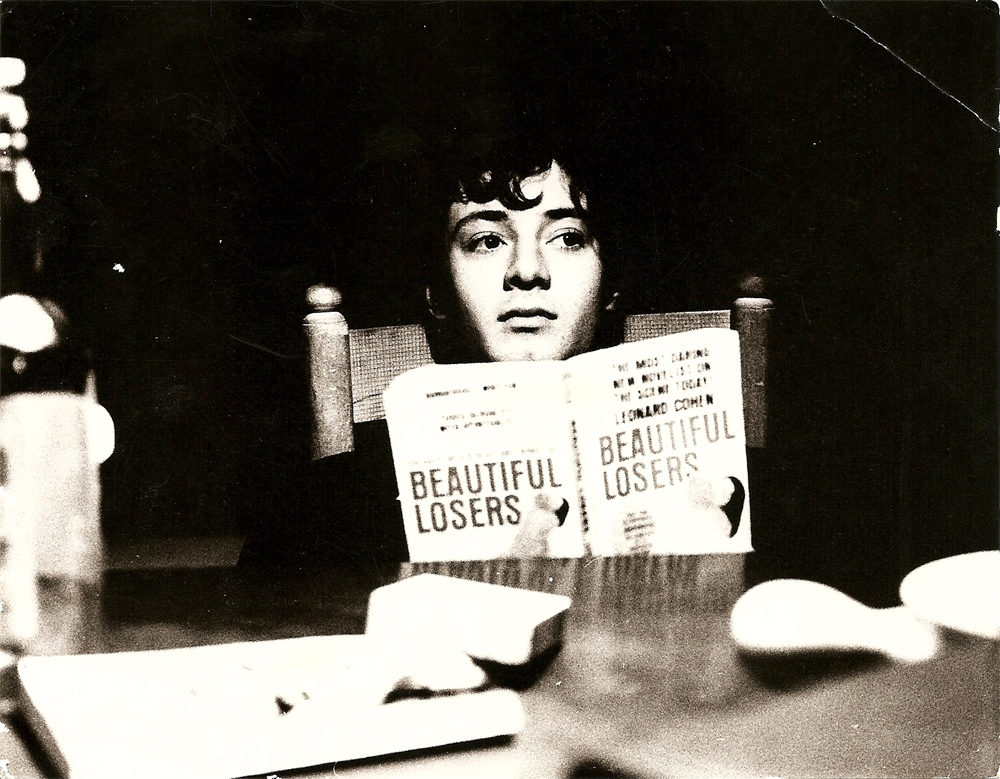

I began curating in 1985 in the United States when I thought that I should have a salary to support my family. Since the only thing I knew was art, it was a short leap from one side to the other. At the time, a curator’s job was not a sought-after one. I applied for a position in springtime to replace a curator who wanted to leave her job in Philadelphia. During the interview, she actually asked me why in the world I wanted to be a curator at the school. Her name was Ann Jarmusch, sister of Jim, the movie director. I owe thirty years of working in museums to the Jarmusch family, which is really “Stranger than Paradise.” For 22 years, I did not touch pencils or watercolors and worked only on the museum’s side of art. I liked it, and I am grateful that I did. In 2007, I moved back to Athens, the city where I had been most inspired, and began to paint again as if not one day had gone by. As time progressed, I spent more and more time painting. The last show I curated was two years ago in Abu Dhabi. Curating and painting require two different levels of focus. Curating is a discipline: it entails designing exhibitions, catalogs, writing texts, a declared point of view on art and social issues, and a hierarchy of roles. Art is a practice, an obscure and luminous source. I like curating, but painting is like breathing.

Who are your favorite Greek artists?

Giorgio de Chirico and Alberto Savinio, both born and nurtured in Greece. I love Tsarouchis‘s projects for the stage. I am extremely fond of Marina Karella‘s watercolors. I wish I had her skill! Unfortunately, Nikos Alexiou left us too soon. I admire the sense of three-dimensional space of Kostis Velonis. I am always surprised by Maro Michalakakos’s work, ceramics, and works on paper. I love the philosophical approach to art of Nicos Baikas. Dionisis Kavallieratos‘s sculptures are funny and multifaceted, and I like Konstantin Kakanias‘s work. I like so many, and I am sure I am leaving many out.

Important gallery launches, fairs, and exhibitions of international appeal over the last years in Athens make art lovers speak of a cultural revival in the Greek capital. Do you agree, and which are your favorite galleries, hubs, events, and institutions in Greece? Where in this country do you experience and enjoy art the most?

There is quite a bit of fervor in the Athenian art community, artists moving to Athens (causing an occasional shortage of art supplies!), spaces with inventive proposals (Bread by Locus Athens); ARCH are doing great programs; young galleries with good shows. All galleries and institutions have a precise identity. This makes for a varied, lively, generous cityscape for art. In random order: Nitra Gallery, Can Gallery, Eleftheria Tseliou, Eleni Koroneou, Hot Wheels, Rodeo, Artemis Baltoyanni with The Intermission, Rebecca Camhi, Gagosian, and I am sure I am leaving out so many. Also, the Deste Foundation and the gallery that has been my friend and supporter for over 40 years, Bernier/Eliades. I love the Benaki, my ideal museum: the museum for Greek culture. I love the Museum of Cycladic Art for its amazing shows and its atmosphere; I am thankful for everything NEON does – they filled an enormous gap and had us reconsider places, sites, artists. The best. I do miss a young gallery that closed a few years ago, QBox. They made amazing shows: seven or eight years ago, I remember seeing “Known, Unknown, Anonymous and on Death Row.” The show put together artists from all walks of life, including one on death row at the Angola prison in Louisiana (hence the title). The heart of the exhibition was that art can be equally entrancing whether done by major artists (Adrian Piper, Rosemarie Trockel, Ugo Rondinone) or by a minor photographic studio in Athens in the 20s (Tabakopoulos and Foundoulis) or by anonymous artists working in the most humble ways. At Qbox, I also saw the films of Parajanov and Peleschyan. It was an adventurous space, looking at work in a quirky way ahead of time.

How has the pandemic affected your day-to-day in Greece over the last year, and how social distancing challenged the art world in general? Was this tough period a creative one for you?

The pandemic kept me for hours and hours at my studio. I am so privileged to be an artist, one with hardly any needs: paper, colors, sunlight, and a large table. The situation is much different for galleries and museums, and for all of whom contact is an integral part of their profession. Dancers, actors…

You have spent a lot of time in the islands (Schoinoussa, Sifnos, Kythira, Sikinos) throughout the years. You even thought about spending your life in one of them with only 30 residents. Can you share with us a few of your stories and memories?

So many! In Schoinoussa in 1992, I heard so many wonderful stories; there was a long and deep local lore. Here is an island legend that was recounted at the time: There was a very attractive doctor who was particularly gentle and kind. (This I know first-hand; my 7-year-old son wanted to go see her at the smallest cut or twist of an ankle, completely besotted by her). Rumor has it that one of the cow herders of Mersini (the 30-people village in the center of the island) fell in love with her. One night, after generously drinking “karafakias” and “karafakias” (small bottles) of homemade tsipouro to summon courage, he arrived at Chora with all the cows and bulls he owned, twenty or more of them. One can only imagine the bellowing, the sound of the hoofs and bells in the dark night. He lead them to the “sokaki” (cobblestone path) where the nice doctor lived, and, under her window, he promised eternal love, telling her (in a rather loud voice) that he had brought his fortune to lay it at her feet. She was quite startled and afraid; fortunately, a neighbor summoned the owner of the MiniMarket, who had a nautical CB (there were no functioning phones on the island at the time). He promptly called the police in Syros (there was no police in Schoinoussa); the Syriot police asked to speak to the forlorn lover on the CB. They told him he was under arrest for disturbance of the peace and had to take the first inter-island ferry, the “Skopeliti,” the next morning and present himself at the police station in Hermoupolis to be arraigned – which he did. It was the first-ever arrest that I heard was done over the phone! Another memory was from Leipsoi in 1990. One evening at sunset, I saw a shepherd on a mule, howling to the far valleys and gorges. Little by little, sheep and goats appeared out of nowhere and gathered around him. I had witnessed something as ancient as Greece, an event that probably had been taking place since the time of Homer. It is etched in my soul; I remember the scarlet sunset, the carob trees on the hills, and that haunting voice that spoke of friendship between man and beast. I am grateful to have witnessed what was probably one of the last examples of this ancient art. As for the 30-people island… It was the July of 1991, and from Leipsoi, I went to Arkoi on a day trip. Fell instantly in love with the island. When I suggested that we move there for the rest of the summer, my wife threatened divorce!

Any special projects or plans in the islands?

With my friend Alexis Tsiantis, we are trying to save the former Negroponte Mansion in Ermoupolis, in Syros. It is a beautiful building in the heart of Vaporia, built in 1856, a patrician home with frescoes, uninhabited for the past thirty years. It needs major restoration. All this with the goal of opening it to the public as the seat of the Cyclades Drawing Center – an institution devoted to researching, preserving, and exhibiting works on paper, the fourth independent “drawing center” in the world (after New York, Paris, and London).

You are an Italian, living among many countries (Switzerland/France/Italy/ Turkey). Why do you prefer Athens the most?

I simply love Athens; it was love at first sight!

What would you say of your affinity with Greek music and poetry?

My love for the poetry of Seferis played the main role in wanting to move to Athens. I also loved Greek music. In 1970 I was in Ios island (pre-hippy Ios), and in the Chora there were two taverns, Yannis and Electric Yannis, the latter because he had a juke-box. This is where I heard “Gelmenden” by Yannis Papaioannou for the first time, a “pastourmas” song in tentative Turkish. The riffs by 70-year-old Papaioannou were something of the likes of which I had never heard. At the first notes, I was won over. A long and faithful love with Greek music ensued, thanks to 10 drachmas into a machine and the welcoming den of Electric Yannis.

Your paintings are sober and delicate. How has the Greek spirit influenced your work?

I have an affinity with the austerity of Greece, at least with the value that is attributed to being “mazemenos,” meaning “collected,” as seen in dance. The sobriety of gestures, the clarity of vernacular architecture, the simplicity of food, the kindness of offerings – a candle in church, a fruit to a wanderer; Greece is unique in this way.

Through your work, it seems you like animals. I am particularly thinking of a little donkey I saw in your drawing…

I love donkeys, cats, dogs, hedgehogs… For a few years before she passed away of old age, I supported a donkey, Agapi, at the Agia Marina Donkey haven in Crete, a wonderful rescue center founded by the kindest couple. (Please support a donkey!) I love my stray cat Ploutarhos, whom I feed and caress every day when I am in Athens. A true gentleman with wonderful Athenian cat conversation.

Have you ever used the Aegean seawater to paint? I know that salt is not making the drying easy…

Such a lovely idea! I wish I had. One day. Thank you, Stéphanie!